Nothing illustrates what we do better than seeing objects before and after treatment. Click on any image to see a larger view.

Unknown Artist (American), Portrait of a Man, ca. 19th Century, Oil on Canvas, Private Collection

The first steps in this painting's treatment was to consolidate the insecure paint by introducing an appropriate adhesive into the cracks. Planar distortions were corrected by removing the painting from the stretcher and giving an overall humification treatment. The weakened canvas was then reinforced with a lining of a strong synthetic fabric before being remounted onto the original stretcher. The complex cleaning proceeded in stage using tailor-made solutions to remove the grime, then the discolored and blanched varnish, then recalcitrant stains. The depth and saturation of the colors were recovered. After application of a stable protective varnish, the few losses were inpainted to match surrounding original paint, and the portrait regained its intended distinguished appearance.

Unknown Artist (Spanish), Reliquary Bust, ca. 16th Century, Polychrome Sculpture,

Hearst Castle, California State Park

Hearst Castle, California State Park

When the bust came to BACC, it was clear that it had previously been treated with wax to stabilize flaking paint, but unfortunately, the wax held the paint in a misaligned position and had imbibed grime over time. There was an older grime layer beneath a discolored varnish layer, and old losses were covered with darkened restorer's paint. Pieces of wood were missing from the necklace and base. BACC conservators began by realigning paint flakes using a tacking iron and conservation-grade adhesives. The artificial surface coating and underlying layer of wax and grime were then carefully removed. The missing ornamentation at the base and part of the necklace were refabricated with clay, cast in epoxy putty and then adhered to the artwork. Losses were filled and toned with reversible conservation paints. Now, the bust is stable, clean, and ready to be enjoyed by all.

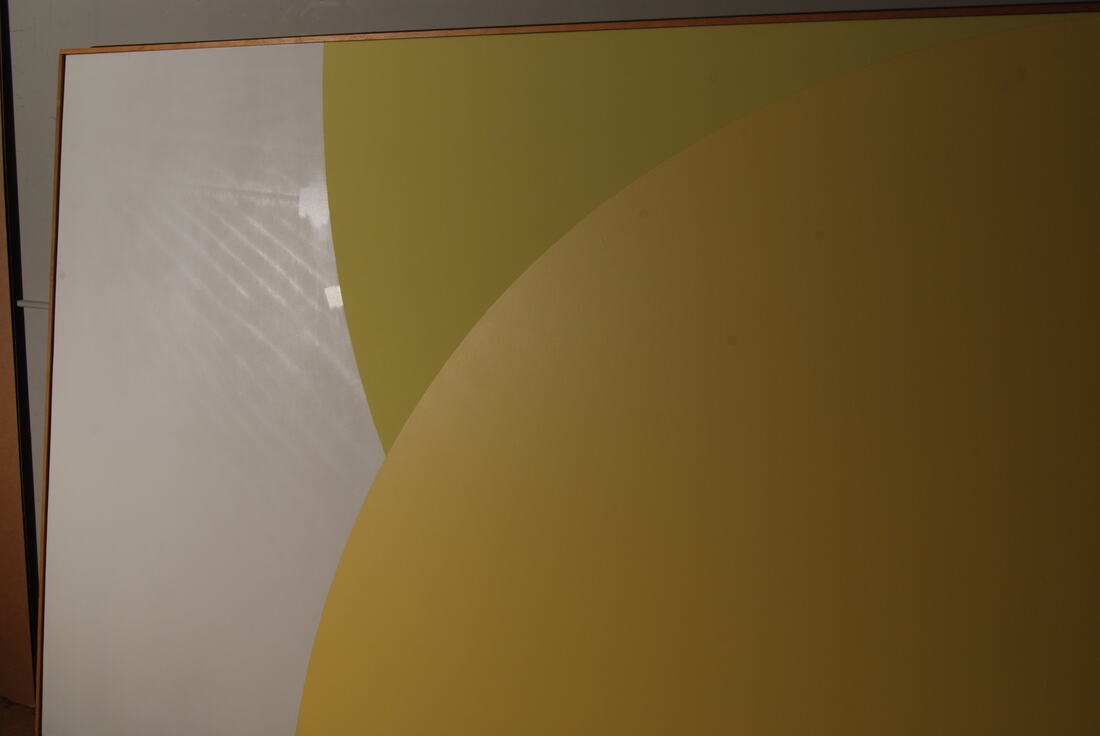

Darby Bannard (American, 1934 - 2016), Yellow Rose #7, 1965, Acrylic on Canvas, Private Collection

Cleaning an acrylic painting is complex due to the nature of the paint. Acrylic emulsion paints are comprised not only of pigments and binder, but also surfactants, freeze/thaw agents, and stabilizers. As acrylic emulsion paints age, it has been found that the surfactant component can migrate to the surface, creating a hazy appearance. In addition, acrylic paintings often do not have the protection of a varnish layer, they are much more sensitive to water and organic solvents than oil paint films, and their surfaces are somewhat sponge-like causing dirt to become easily ingrained.

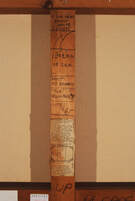

This painting had an uneven layer of migrating surfactants and ingrained grime that changed the surface sheen of the paint. After initial testing, the uneven surfactants that were causing the diagonal radiating lines in the white and yellow gloss paints on this piece were removed using smooth cosmetic sponges and a solvent. The resulting glossy paint surfaces now more closely resemble what the artist initially intended for the painting, as indicated by the notes Bannard left on the stretcher verso (see photo, above). The matte yellow paint at the top did not have surface irregularities and was found to be too sensitive and therefore was left as is. The verso of the stretcher was gently dusted. A protective backing board was attached to the reverse of the stretcher, as well, to complete the treatment.

This painting had an uneven layer of migrating surfactants and ingrained grime that changed the surface sheen of the paint. After initial testing, the uneven surfactants that were causing the diagonal radiating lines in the white and yellow gloss paints on this piece were removed using smooth cosmetic sponges and a solvent. The resulting glossy paint surfaces now more closely resemble what the artist initially intended for the painting, as indicated by the notes Bannard left on the stretcher verso (see photo, above). The matte yellow paint at the top did not have surface irregularities and was found to be too sensitive and therefore was left as is. The verso of the stretcher was gently dusted. A protective backing board was attached to the reverse of the stretcher, as well, to complete the treatment.

Pietro Perugino (Italian, ca. 1450 - 1528), St. Jerome in the Wilderness, ca. 1510-1515,

Oil on Panel, San Diego Museum of Art

Oil on Panel, San Diego Museum of Art

Click to watch a YouTube video to learn how BACC and the San Diego Museum of Art discovered the lost crucifix in this painting by Perugino. It's a wonderful example of the important role conservation work can play in uncovering art historical information.

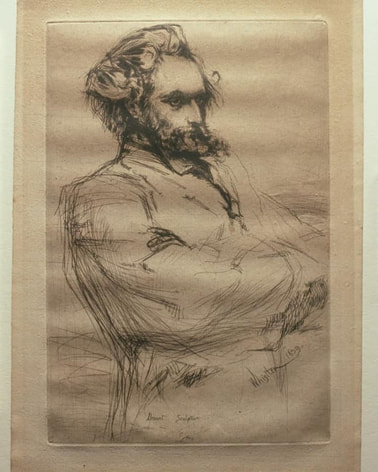

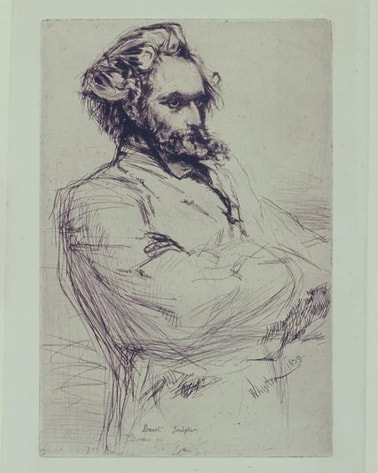

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903), Drouet Sculpteur, 19th Century,

Etching in Drypoint, Private Collection

Etching in Drypoint, Private Collection

The treatment goals for James McNeill Whistler's Drouet Sculpteur were to improve the appearance of the print and the stability of the paper by reducing discoloration and bringing deterioration products in the paper down to a minimum. Previous hinges were removed, and adhesive was reduced to a minimum. The print was bathed and alkalized to neutralize acids. Stains were removed as well as possible. Whistler's printing notes were revealed at the top right "Whistler Maitre Eaufortier" after discoloration was removed, as well.

Belle Baranceanu (American, 1902 - 1988), Mission Hills, ca 1930, Oil on Canvas, San Diego History Center

Antonio de Bellis (Italian ca. 1616 - 1660), David with Head of Goliath, ca. 1642-43,

Oil on Canvas, San Diego Museum of Art

Oil on Canvas, San Diego Museum of Art

Our conservation treatment uncovered the head of Goliath (lower left), which had long ago been covered with overpaint.

Edwin Lord Weeks (American, 1849 - 1903), Market Scene at Mogador, ca. 1881,

Oil on Canvas, San Diego Museum of Art

Oil on Canvas, San Diego Museum of Art

The San Diego Museum of Art's 19th century painting Market Scene at Mogador by Edwin Lord Weeks was brought to BACC to aesthetically improve the painting. A discolored natural resin varnish both gave a yellow cast to the painting and visually flattened the depth of the composition by reducing the original contrast. In addition, overpaint from an old restoration had discolored, causing areas of the original composition (especially the clouds in the sky) to look murky and incompatible with the original paint. After initial testing, BACC determined the safest, most effective way to remove the discolored varnish and overpaint. After many hours of careful cleaning, the original colors and paint passages of Temple at Mogador were revealed. Most notably, the jewel-like blue of the sky became visible and the original, sophisticated color relationships created depth in the image once again. A reversible, protective coat of synthetic varnish (which will not discolor!) was applied to the surface, and the painting was returned to the museum.

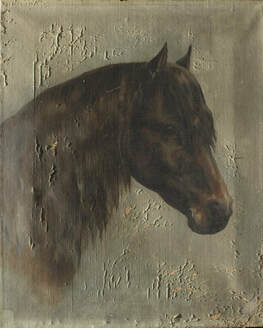

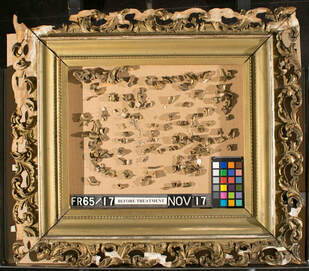

Unknown Artist, Portrait of a Horse, Oil on Canvas, Private Collection

The delicately rendered Portrait of a Horse, part of a private collection, came to BACC to be treated for paint loss and lifting paint caused by water damage. In addition to the structural damage, the painting also had a heavy grime and discolored natural resin varnish layer that disfigured the original colors and tones of the composition. BACC conservators were able to stabilize the paint, return cupping paint back into plane, remove dirt, grime, and old varnish from the surface, fill and inpaint losses to the composition, and saturate the paint colors with a new, chemically stable varnish. The frame for Portrait of a Horse came to BACC in pieces due to inherent structural instability of the original materials. The BACC team was able to put the puzzle pieces back into place, and BACC's frame conservator reconstructed lost ornamentation, filled losses, and in-gilded losses to match the existing bronze finish.

Andries Vermeulen (Dutch, 1763 - 1814), Winter in Holland, ca. 19th century, Oil on Canvas, Private Collection

After removing Winter in Holland from the stretcher, the canvas around the large complex tear on the right side was carefully flattened, and the broken threads were realigned and mended from the reverse just along the break. Because the canvas was so brittle, it was reinforced with an overall lining of a strong synthetic fabric attached with a reversible, non-penetrating adhesive. Removal of the discolored varnish revealed the artist's intended clear colors and overall cool tonality, allowing the snow and ice to sparkle and contrast with the warm color of the houses. The small amount of loss along the tear was carefully inpainted to reintegrate the surface.

Video extras

In this video series, Chief Conservator of Paintings at BACC, Alexis Miller, and former Curator of European Art at SDMA, John Marciari, discuss the role of conservation in uncovering art historical information about works in the collection of the San Diego Museum of Art.

|

Finding the Lost Crucifix in a Perugino Panel Painting

|

Examining a Veronese with XRF Spectrometry

|

|

|

|

|

Finding the Original Context of Rosselli's Kneeling Angel

|

What X-Rays of a Vivarini Reveal About Its Past

|